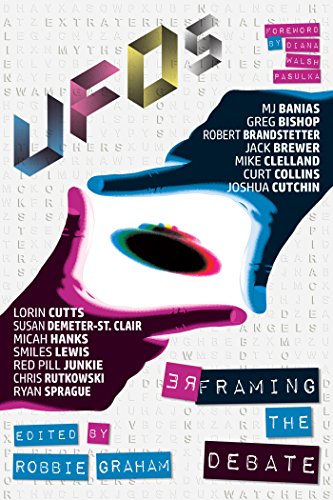

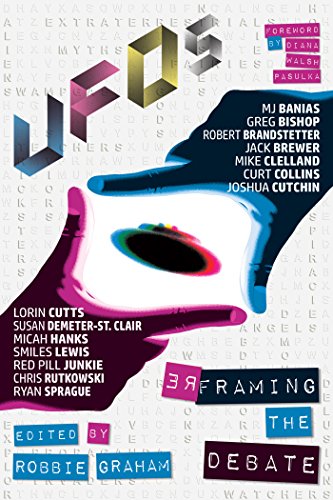

This is Robbie Graham’s intro chapter to his recent anthology — even more needed now that we have all this ‘TicTac’ ‘UAP’ evidence & the whole threat shpiel coming from Pentagon Spooks & their Pop Propagandist Tom DeLonge. We pretty much agree with Graham’s every word, at least up to the summaries of individual chapters. Honestly, this stuff should be in all caps and underlined. Greg Bishop, with one chapter, is another importance voice in the skeptical & more multi-dimensional approach, for which Keel & Vallee laid the ground (all hail Keel & Vallee! & don’t forget Fort and Jung!). Will update once we’ve read the whole dealio. Thx @Robbie!

————————————————————-

Ufologists speak often of “The Truth.” It’s out there, they insist, and it must doggedly be pursued for the benefit of all mankind. But rarely are ufologists truthful with themselves. There is, of course, no such thing as “ufology,” not in any meaningful sense of the term. If “ology” refers to a branch of knowledge or learning sprung from organized research, then ufology is a broken twig.

The UFO field has produced thousands of dedicated researchers over the years, and reams of literature; but to what end? What can we claim to know conclusively today about the underlying nature of UFO phenomena that we didn’t know in the late-1940s? UFO study has always suffered from major organizational and methodological problems. It has also become dangerously self-referential. Few researchers are prepared to think critically.

Today, as ever, the Extraterrestrial Hypothesis (ETH) is the most popular ufological theory. It has become so popular that the already-flimsy architecture of the field has morphed into “exopolitics”—a movement born of the Internet and based on a blanket acceptance that UFOs are extraterrestrial vehicles, that the government knows this, and that, in time, “Truth” will break free and a new age of human enlightenment will begin. It is a myth, spun partly by external design, but largely by the UFO community’s profound need to believe that universal truth is tangible, and within arm’s reach. Today’s UFO conferences bear an increasing resemblance to the spectacle of the Megachurch, where the cult of personality attracts thousands of believers, all hopeful their prophets can move them just an inch closer to UFO salvation.

If ufology is a New Age religion, then “Disclosure” is its Holy Grail—that ever-imminent announcement from officialdom that we are not alone in the universe, and, moreover, that “They” are among us. The problem with the Disclosure mindset is that it declares an end to the UFO enigma and discourages us from further study of the phenomenon, and of its cultural and societal effects. Why study when we can simply wait? All we need do is talk about UFOs in online forums and occasionally send a petition to the White House. Eventually, our leaders will see fit to share with us the aliens’ world-changing information and technologies, ushering in a new era of cosmic consciousness. It’s only a matter of time. Disclosure requires little more than our passive spectatorship.

The ultimate irony of the Disclosure movement is that, by imagining all answers to the UFO mystery to be out of public reach, deep in the bowels of the national security state, it places power into the hands of officialdom, while disempowering the individual. Modern “ufology,” therefore, is no longer about asking challenging questions. Rather, it is about fitting predetermined answers into an established quasi-religious belief system.

If ever we are to further our understanding of the UFO enigma, we must fundamentally reframe our debate. We must wipe the board clean and fill it with new ideas, new theories, even new language. We must be willing to start from scratch when the field stagnates. We must be critical, sober, and free from dogma—ready to rinse away the residue of our own beliefs.

With the above in mind, in April 2016, I began approaching a select few individuals in the UFO research community—free-thinkers and iconoclasts—with a proposal for a volume of original essays presenting alternative perspectives on UFOs and the UFO subculture. Just under a year later, I find myself writing this introduction for the near-complete manuscript. It all came together relatively quickly and smoothly, if not without the usual amount of effort and sacrifice that goes into such an endeavor. All those who chose to write for this volume have committed to it wholeheartedly, and I have been inspired daily by their enthusiasm for the project.

I know I speak for all contributors here when I say this book was a challenge to write. I know it was a challenge to edit, and I also know it will be a challenge to read. Whether you’re a “skeptic” or a “believer” (for lack of more nuanced terms), this book will irk you. And that, of course, is the intention. Indeed, it is structured such that it may provoke maximum discomfort in the reader and push cognitive dissonance into overdrive. For the first half of this volume, the essays spar back and forth between pro-and-anti-materialist approaches. Some of our contributors advocate extreme skepticism of any UFO claim, while championing traditional scientific methodologies—the dispassionate pursuit of objectively verifiable evidence—while other contributors see limitations in such an approach, preferring instead a more oblique path of engagement with what they see as a consciously oblique phenomenon. Other contributors explore why modern UFO accounts seem often to overlap with other mysterious phenomena, or how the UFO can be utilized as a looking-glass for profound introspection, one reflective of personal belief, stress, or trauma.

For all the unconventional theories presented herein, none of the contributors would be so bold or naïve as to discount the possibility that some UFOs are representative of extraterrestrial intelligences. We are suggesting, however, that today’s UFO field is sorely lacking in meaningful debate and is close to the point of stagnation in its uncritical thinking and lazy acceptance of what may seem like the most logical theory for inexplicable aerial anomalies, but which, when tested against the full depth of data, falls desperately short as an exclusive hypothesis. To quote SMiles Lewis in this volume: “I advocate for a multi-theory interpretation of the UFO phenomenon. I don’t think there is any one explanation that accounts for all the data. I think there are a number of things going on simultaneously.”

Many of these “things” undoubtedly stem from what Susan Demeter-St. Clair refers to as “the one clearly tangible vehicle central to any UFO story”—the human witness. The role of the witness in UFO events typically is overlooked by UFO investigators, whose focus often is on what the witness has seen, rather than why they have seen it, or how they have interpreted it. The assumption, strangely, is that UFO witnesses are almost always independent of their anomalous experiences. Multiple essayists in this volume urge a fundamental redirection of UFO research, from the external to the internal—by seeking to understand the daunting complexities of human cognition and consciousness itself, we may better understand the UFO, and, perhaps more importantly, better understand ourselves.

If by some slim chance this is the first UFO book you’ve ever picked up, I’m afraid you’ve thrown yourself in at the very deep end of the pool, but that’s all the more reason to push on with it; if you do so, I feel confident in stating that the wider ufological waters will seem clearer and more navigable.

Chris Rutkowski’s opening essay is a trial by fire for any reader who considers themself a UFO experiencer. He pulls no punches in his characterization of a substantial portion of the UFO community as “zealots.” I know for sure that some readers will be inclined to set this book aside after just a few pages of Rutkowski’s essay. Don’t do that. If his perspective does not fall in line with your own, simply accept that from the outset, proceed with an open mind, and then ask yourself if any of his observations are objectively untrue. Rutkowski’s essay is incisive and, to my mind, necessarily harsh. It is not, as some will undoubtedly see it, a piece of debunkery. Rather, it is a product of its author’s frustration at those UFO enthusiasts whose wholesale rejection of all evidence at odds with their own beliefs justifies his view that ufology is more a religion than a science.

I’ve frontloaded this book with pieces on religion because the religious aspects of UFO belief are undeniable (again, this observation should not be interpreted as a dismissal of UFOs as an objectively real phenomenon. No one in this book attempts to make such a case). Make no mistake, ufology is a New Age religion; with this in mind, its followers should take caution, for many if not all strains of religious belief have been exploited throughout the ages by elite power structures for reasons of cultural and societal control—a case made by several authors here.

If UFO “believers” can pass the test of Rutkowski’s essay—if they can override their cognitive dissonance—then they have the resilience and critical thinking to see them through all the essays that follow.

Next up, and in sharp contrast to Rutkowski’s, Mike Clelland’s essay is a deeply personal meditation on the author’s direct experiences with UFOs and what he considers to be some form of non-human intelligence. Those of a traditionally skeptical bent may be inclined to skip Clelland’s essay. Don’t do that. Clelland’s value in this volume is that he is unusually self-aware and self-analytical in the presentation of his experiences. He is certain he has interacted with anomalous phenomena in mysterious ways, but he steadfastly refuses to reach solid conclusions as to the ultimate nature and purpose of these phenomena. Clelland is an “experiencer” who shuns zealotry and who wears with discomfort any ufological labels that might be used to categorize him. He is compelled to share his story, and he wants us to hear it, but he also wants us to know he is incapable of objectivity in this arena. If more experiencers could adopt Clelland’s considered approach, perhaps some bridges could be built between opposing ends of the UFO research camp.

Clelland’s observations are largely subjective, and he places great value on the experience of the individual UFO witness. In contrast, the observations of our next contributor, Jack Brewer, are rooted in rationalism and the scientific method. Brewer seriously questions the value of UFO witness testimony, noting “…personal stories, interesting and entertaining as they may be, are often of very little value to the professional research process.” He goes on to qualify this statement in considerable detail.

Brewer’s essay is broad in scope and among the most constructive in this volume. It highlights numerous problems currently hampering serious UFO research, and then provides possible remedies and solutions. Again, it is the work of a man with a deep interest in the UFO mystery and a deep frustration at the lazy assumptions and shoddy practices of a great many—perhaps the majority—of UFO researchers.

Next in our line-up is Joshua Cutchin. Continuing with our back-and-forth approach, Cutchin’s essay is a bold rejection of traditional materialist solutions to the UFO riddle and a challenge to “nut-and-bolts” researchers to engage with “high-strangeness” aspects of UFO phenomena from unconventional—even esoteric—perspectives. He encourages that we embrace uncertainty, noting: “Moving beyond materialism is about honestly confronting the fact that we know nothing for certain about UFOs, yet choosing to be inspired rather than frustrated by this realization, leading to a type of non-dogmatic gnosticism.”

We’re back to a materialist approach in Micah Hanks’ contribution, which champions rigorous scientific methodology and ambitiously seeks to provide an entirely revised classification system for UFO reporting in the hope of more effectively sorting the proverbial wheat from the chaff. Still, Hanks seeks a union between those who operate within the structures of modern skepticism and those who roam beyond its walls, and he warns against scientific dogmatism, noting: “Modern skepticism can, I think, be summarized in many instances as an ideology, around which a social movement has been built—one that, today, also runs tangent with atheism—and as a paradoxically evangelical attitude about the supremacy of science above all other forms of knowledge.”

We tread a middle ground in Lorin Cutts’ essay, which acknowledges what its author considers to be a genuine mystery behind the UFO phenomenon, while advocating extreme skepticism towards almost all aspects of ufology. Cutts propounds similar ideas to those of Diana Walsh Pasulka and Jack Brewer in his discussion of what he refers to as the UFO mythological zone: “the gap between fact and belief, what we see and what we want to see, what we experience and how we interpret it.” Cutts, himself a UFO witness, seeks to highlight what he sees as the major obstacles we must overcome—or at least recognize—if we are ever to come close to understanding the UFO enigma. The biggest obstacle, suggests Cutts, is us—our enthusiastic willingness to believe and to be led. He notes: “Many people are highly malleable and susceptible to new ideas and beliefs within the UFO mythological zone. Charlatans, fraudsters, and hucksters are free to roam and operate at will. Their contribution to the UFO subject should never be underestimated, for the conditions for successful deception are near perfect. Common sense, lateral thinking and balanced questioning are far superseded and outweighed by irrational belief. Contagion of ideas is rife.”

Narrowing our focus in this volume is Curt Collins, whose essay is devoted entirely to documenting the skeptical investigation and successful debunking of the so-called “Roswell Slides,” which were purported to show the image of a deceased alien entity. Collins was one of several members of the Roswell Slides Research Group (RSRG), and his contribution here is the definitive accounting of how the RSRG operated in tackling one of the greatest ufological blunders (or hoaxes, depending on your perspective) of the 21st Century. Collins’ essay is intricate in its detail and reads like a true-life detective story of how a handful of researchers, separated in some cases by thousands of miles but united in cyberspace, took it upon themselves to expose as fraudulent the claims of dubious UFO personalities screaming from the hilltops that they had found the smoking-gun for Roswell, and that UFO Disclosure was now just a step away.

The reader can make up their own mind as to what motivated the Slides’ promoters, but, for me, this was less a conscious hoax, and more a case of blind belief. The promoters wanted so desperately for the “evidence” to fit their firmly-established perspective on Roswell and UFOs more broadly, that they fooled themselves completely, seeing only what they wanted to see. And they fooled a great many UFO enthusiasts and researchers in the process. When the truth was exposed—that the Slides showed not an alien body, but something entirely down to Earth—it felt to many like the final nail in the coffin for popular ufology. Certainly, it can be said that the Slides debacle represents everything that’s wrong with “ufology” today.

Collins presents the RSRG investigation here as a potential model for future UFO research and investigation—an example of how researchers can work together to solve definitively certain cases and prevent the spread of misinformation in the field. Collins reflects on the strengths and weaknesses of his group’s methodology and observes: “Groups can be great tools, but they have their limitations. Each of us must remain objective, seek the best evidence and ask challenging questions, whether as part of a team or as individuals.”

Next up is SMiles Lewis’ adapted transcript of an epic public lecture he delivered, examining “The Fantastic Facts about UFOs, Altered States of Consciousness, and Mind-at-Large.” It’s a wide-ranging and deeply insightful piece covering everything from Gaian consciousness and planetary poltergeists, to the possible use of the UFO for “Covert Folklore Warfare” by government spooks. It also serves as an extensive bibliography of obscure but valuable literature relating to all themes explored throughout this book. For esoteric and conspiratorial bookworms, Lewis’ essay is a treasure-trove.

We then move to MJ Banias. His ambitious contribution examines the limitations of subcultural UFO discourse within the constraints of modern capitalism. He argues that the ideologies of capitalism and UFO discourse are fundamentally at odds, and the result is that “ufology is forever trapped in a marginalized state.”

Banias notes that, in stark contrast to the capitalist citadel under whose shadow it chaotically dances, UFO discourse has “no locus of control, no elites, and no ivory tower that establishes ideological truth. There is no established power in the discourse, therefore power moves openly between constant shifts in ideas.” The UFO discourse, Banias argues, has no mechanism of governance: “it is democratized, with members of the subculture able freely to express their own ideologies, which vary from reasoned logic to utter speculative hokum… It is, in simple terms, a field of study which is completely democratized. It is an example of a living and functioning discourse that counters modern ideological capital—it creates a pseudo-reality that does not require mainstream official ideologies in order to exist; it is in this democratic state where modern ideological capital is impotent, unable to entrench itself and establish ideological order.”

Unfortunately for ufology, it is this same dynamic that prevents even serious and legitimate UFO discourse from ever finding its way into official culture as anything other than a sideshow attraction. The future of ufology is bleak, says Banias, observing that, in the event of some form of official UFO “Disclosure” (if such a thing is even possible), “ufology would die an instant death as the entire subject would quickly become negotiated into the general sciences and, therefore, into capitalist ideological structures. If we assume that the status quo is maintained, and there is no public announcement… ufology will remain where it is. What can only occur then is a grassroots movement which always operates against the current ideological reality.”

Continuing the sociological line of enquiry, our next contributor, Red Pill Junkie (RPJ), refers to the UFO phenomenon as a “disruption.” Expanding on the theories of Jacques Vallée and John Keel, RPJ considers the possibility that UFO events may be the product of a trickster intelligence, gleefully and anarchically prodding us to provoke individual and societal reactions and developments. He notes, “The UFO disruption is not only a threat to the authority of scientific orthodoxy, it fundamentally defies every conceivable paradigm human society is built upon, in almost every sphere one can envision: religion, economics, communication, and state politics, to name but a few.”

Equally, RPJ also considers it possible that certain UFO events are psychically-manifested by-products of collective stress and trauma during times of societal pressure or upheaval. Regardless of its possible stimuli or motivations, says RPJ, the UFO is the ultimate symbol of anarchist subversion in the modern world. Beyond its cultural and sociological musings, RPJ’s essay is also a personal reflection on how its author has utilized the UFO as an instrument to better understand his own worldview in relation to others.

Susan Demeter-St. Clair’s contribution is a focused discussion of how so many UFO experiences appear to overlap with parapsychological phenomena. Like Red Pill Junkie, she also makes a case for certain UFO events—particularly mass sightings—being triggered by the same psychic mechanisms as provoke poltergeist activity; such events, perhaps, being born of personal or social unrest and upheaval. As with others in this volume, Demeter-St. Clair urges UFO researchers to engage more openly and thoughtfully with the high-strangeness aspects of the phenomena. She argues, “UFO reports that include various types of psychic phenomena may be the key to a greater understanding of the UFO enigma, or, at the very least, trigger more meaningful questions in our ongoing efforts to understand it.”

Ryan Sprague’s essay draws from the work of theorists and researchers including Carl Jung, Jacques Vallée, Jenny Randles, David Clarke, and Greg Bishop. It considers the enduring appeal of the UFO in modern culture, ufology’s long (and perhaps futile) struggle for legitimacy, and the questionable inclination of so many UFO researchers to label the phenomenon as “extraterrestrial.”

Sprague does not discount the possibility of otherworldly visitation, but he ushers the reader gently down other avenues of enquiry and suggests we may sooner to come to grips with the nature of the UFO phenomenon by seeking to unravel the complexities of human cognition and our own perceptual apparatus.

Similar ideas are explored in great depth by Greg Bishop. His essay applies advanced theories of cognition to the experience of the UFO witness to highlight the foibles of human perception and how what we see is not necessarily an accurate representation of what is there, especially when we’re confronted with phenomena at the extremities of human experience. The convolutions of human memory are also considered, as are the often-hindering approaches of the UFO investigator when eliciting witness testimony. Bishop notes: “In the act of first experiencing the event, and then, more importantly, in remembering it and telling the story about it to ourselves and others, we are adding many layers of cultural baggage and other input that help us to make sense of the experience. In so doing, we are taking ourselves step-by-step away from our original impressions.”

Like others in this volume, Bishop encourages sharper focus on the role of the witness in the UFO equation. He posits that UFO phenomena may even be “co-created” events between the observer and the observed. This theory allows for the existence of anomalous stimuli or even non-human intelligences, but suggests that whatever the underlying cause of UFO events, it is likely far more complex and participatory than mere extraterrestrial visitation.

“How much do we bring to the dance during a paranormal encounter?” Bishop asks, “How much of the UFO experience is the result of our subconscious minds trying to make sense of unexpected, startling, and/or frightening input, and leaving us with an insane placeholder when it can’t decide on anything else?”

Bishop’s essay builds a compelling case for the power of the human mind to radically distort subjective extraordinary experiences—even in the moment of the experience. It raises serious questions about just how far off the mark popular ufology is in its simplistic conceptualization of this phenomenon.

Grasping for definitive answers to the UFO riddle is perhaps not the most productive approach, says Bishop: “The terms of the search may need to be changed. If we are looking for an ‘answer’ to the enigma, this assumes that there is an easy or understandable one waiting in the wings for just the right researcher who gets lucky or is amazingly smart. Perhaps the process should be referred to as a quest for understanding rather than any search for a specific truth. This may serve to keep the question open, and direct thought processes and models.”

Our final essay, by Robert Brandstetter, again examines the perceptual limitations of the human observer, but it also serves as an impassioned plea for UFO witnesses—who often exhibit signs of real trauma—to be treated with empathy and compassion by those who might otherwise seek to exploit, ridicule, or ignore them. Whatever its root cause, the UFO experience is ultimately a human one, and all that that implies.

Brandstetter observes:

Investigatory approaches towards the UFO witness have been haphazard and, in some cases, quite harmful, leaving the witness as something to both exploit and consume. Yet it is the witness experience that is the primary catalyst for ufology… What started as a story about seeing something strange in the sky has since been manufactured into a mythology… A return to the core component of the narrative is necessary and it must be done with more imagination, ethics and standardization that respect what it means to undergo a traumatic experience. A more compassionate approach to the witness, as well as an appreciation of how the act of seeing works during high-strange experiences, may allow us to gather much more valuable information about how the UFO phenomenon intersects with human perception.

Brandstetter ends his essay, and this volume, with profoundly personal contemplations on what it means to be a UFO witness, and the value of seeking to understand, to know, and to learn from those whose identity is bound-up in the alien Other.

This volume is critical but constructive. It combines ideas both abstract and theoretical, and concrete and practical. Some of these ideas gel and overlap; some of them clash and conflict. The goal is to shift and reframe the debate outside the prison of belief, yet also beyond the razor-wire of scientific dogmatism.

I encourage that you approach this book from the perspective of an anthropologist. Imagine your eyes are fresh to the UFO spectacle. What do you see in these essays? What do they communicate to you, individually and collectively? What do they tell you about their authors? What does your attraction and reaction to this book tell you about you? Pull this book apart. Dissect it. Dissect us. Dissect yourself. Consume every word. Muse on every theme and concept. If you feel riled or uncomfortable at any point, ask yourself why.

I provide no conclusion at the end of this volume because I am reluctant to further stamp myself on the material—I wish for the reader to be as free as possible in their own interpretations—and because I’m not sure there are any meaningful conclusions to be drawn of the phenomenon now beyond the theories and suggestions presented across the spectrum of these essays. Reach a conclusion if you can, but hold it lightly in the acceptance that letting go is no bad thing.

Understanding UFOs and related phenomena is a glacially slow process that is in its fetal stages. The UFO research field would do well to accept and appreciate this. Therein lies the freedom to explore—and to learn.

UFOs: Reframing the Debate is a cold, hard, slap in the face for “ufology,” delivered with love. It is a call to break away from established ideas, approaches, and practices, and to boldly tread a new path in quest of understanding what may very well be the greatest mystery of all.